Media Matters goes beyond simply reporting on current trends and hot topics to get to the heart of media, advertising and marketing issues with insightful analyses and critiques that help create a perspective on industry buzz throughout the year. It's a must-read supplement to our research annuals.

Sign up now to subscribe or access the Archives

There has been a great deal of discussion about how linear TV has lost the younger generations of TV viewers, and it's true that the first to defect to streaming were teens and young adults. These groups have reduced their consumption of broadcast TV and cable fare by 50% or more over the past ten years, due in large part to the quality and predictability of linear TV content. In particular, primetime has suffered sharp declines.

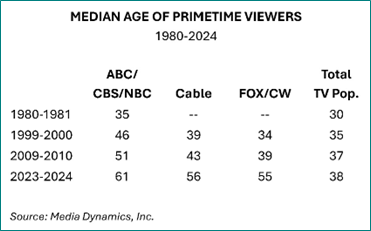

The broadcast TV networks ruled the primetime rating roost from TV's inception in the early-1950s to the 1980s. According to Nielsen the average minute primetime network audience in 1980 consisted of 20-22% teens and children and just below 30% adults aged 18-34. In contrast, the 55+ segment contributed just 25% of the audience. As a result, the median age of their average minute audience was 35 years, which was only five years higher than the corresponding figure for the population as a whole.

But competition from cable, with a plethora of content appealing to younger audiences, gradually impacted broadcast’s lead. And primetime networks led by movie companies like Fox, Paramount and Warner Brothers appeared and counterprogrammed ABC/CBS/NBC with younger-slanted shows. Pay cable also contributed mightily to the onslaught against the big three broadcast TV networks' fading dominance with shows like The Sopranos and Mad Men. Finally, streaming arrived on the scene and, again it was the younger set that flocked to this new medium, especially Netflix and other services that offered "original" content tailored for younger, more sophisticated tastes.

The accompanying table shows the results of this long ranging battle for younger viewers, which has seen the median age of the ABC/CBS/NBC networks go from 35 years in 1980 to 61 years today. Not surprisingly, while the cable channels and the movie networks both started out with very young viewers relative to the big three, their audiences also aged over time. At first, cable took away younger audiences, then the movie networks arrived and stole more of the big three's young fans, but also took away some younger cable viewers so the cable audience also began to age. Most recently, streaming has done the same thing to both cable and the broadcast movie networks (currently Fox and The CW) and their audiences have aged significantly (see table).

From the broadcast TV networks’ standpoint (including Fox and The CW) the attrition among the younger set—both 18-34s as well as teens and kids—has been tremendous. They have virtually no teen and children viewers left and if one was targeting young adults the choices are few and far between. We recently conducted an analysis of 123 primetime shows for all five networks and found that 62% of them had a median age of 60 years or higher while 30% fell into the 55-59 age group. This left only 8% of the shows with "younger" audience profiles but even here none of these few shows had median ages lower than 45 years. As a vestige of former times, all of the "young appeal" shows were offered by Fox or The CW, including The Simpsons and Family Guy.

How did we get here?

Complacency is partly to blame. The broadcast TV networks have always equated size with quality, therefore if their shows reached on average 18% of all TV homes per telecast while their top rated shows fared almost twice as well, they scoffed at cable's puny ratings (typically .5% of all TV homes with peaks of 1%) seeing cable as weak competition and not to be feared. Also, the three broadcast networks had firm control of the TV marketplace and very strong ties to the time buying community, so what was there to worry about?

It turns out there was a lot to fear, just not immediately. It was obvious to any neutral observer that even if the average rating for the cable channels was a mere .5%, if 50 of these channels were averaging a .5% per show tune-in, that represented a total audience of 25%, which was a potentially serious problem for ABC, CBS and NBC. And that is more or less what happened, only—once they woke up to the threat—the major networks acquired many of the top cable channels or started their own, thereby gobbling up many of their would-be competitors. This became very profitable as they used a two-revenue-streams model, ads plus carriage fees paid by the cable systems and satellite distributors.

Meanwhile Fox and The WB retained their younger slant well into the 2000s. And then Netflix arrived and, thanks to the stupidity of the major networks, offered competition by shunning ads, funding original productions and obtaining large libraries of quality off-network fare, with the concurrence of the networks who were partnered with producers of hit shows like Seinfeld and shared in any syndication sales. Evidently, it never occurred to the networks that by garnering millions of dollars in syndication sales from Netflix that they were providing it with the means to lure away their viewers, especially the younger ones who were watching these “classic” shows for the first time. The networks and, eventually, their cable and movie network competitors, continued to do business with favored program producers, often in syndication sharing partnerships. This led to endless extensions of popular shows (e.g. NCIS) that featured essentially the same programming, except with new casts in new locations. Syndication interests also led to the networks renewing shows that had overstayed their welcome in the hopes of making still greater rerun profits thanks to additional episodes.

When the broadcast TV networks finally decided to enter the streaming arena, they tried to limit the competitive influence of Netflix by not renewing many of the off-network shows that had been licensed to it. But when it came to their own streaming platforms, they again equated size with quality and sought the maximum number of subscribers, even if the cost of attainment would be very high. They spent heavily to outdo Netflix with their own originals only to learn that this was an approach that denied them profitability. This is because, as we have explained in many of our reports, streaming has not captured all of linear TV's viewing, only about 35-40% of it. And the number of players in streaming has risen to the point where there simply isn't enough viewing time to support all of them. So now the networks are charting new courses as they try to make their streaming ventures profitable, including cutting program costs, selling ads or offering subscribers hybrid options with or without ads. As for those pricey originals, they have not paid out, ROI-wise, so their production is sure to decline.

What is likely to happen is that linear TV will morph to include streaming. The networks, channels and services that survive the great shakeout that is coming will have to face the basic reality that has always applied: namely, that younger consumers watch substantially less frequently than older ones. This means it's going to be very difficult to capture and retain younger, always fickle audiences without experimenting with unusual—and risky—program concepts and accepting the fact that even if the loyalty of a younger viewer is obtained one season, it may be lost the next year when a competitor offers something new and trendy.

The best approach for the networks is to create balanced program schedules at affordable costs and use a variety of fare to cater to different ages and mindsets, rather than chasing a single demographic. We will see how the programmers handle these new challenges and whether anything has been learned from past experience.

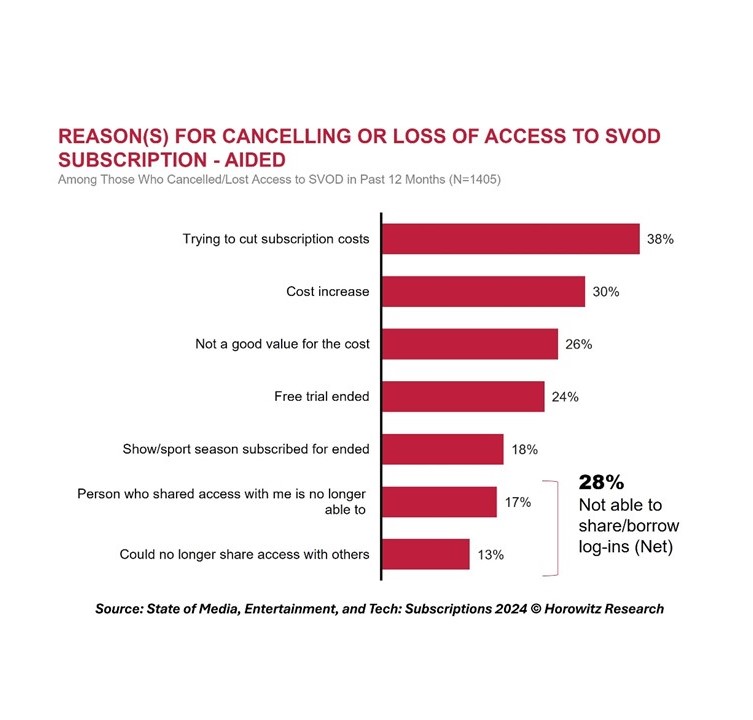

Over one-quarter (28%) of respondents who cancelled or lost access to a SVOD subscription in the last 12 months reported that it was because they were “not able to share/borrow log-ins”, according to a 2021 Horowitz Research survey. Streaming giants, however, seem unphased. According to Forbes, Netflix added nine million new subscribers following its password sharing crackdown, and 30% of these were for its ad-supported plan. That’s a win-win: more subscription revenue and more eyeballs delivered to ads running on its AVOD service. It’s no wonder that other major streamers, including Disney+ and Max, are now following suit. For now, it seems 28% is nothing to lose.